Presley King moved from the small Grenadian island of Bequia to Tortola in 1967. He was 23 and worked with his cousin transporting freight between Puerto Rico and the Virgin Islands. One day, as he sailed passed Fajardo on a 55-foot monohull, Presley noticed the boat had lost its rudder. Instead of flagging down help or calling the Coast Guard, the seasoned seaman canvased the vessel. He found two truck tires. Securing one tire to each side of the boat and alternately using them as drag, Presley was able to navigate his crew and freight the 50 miles back to St Thomas—and successfully bring the boat to parallel-parked safety in the marina.

It’s these inherent abilities to understand the relationship between a boat and the sea that have made Presley a decorated and celebrated sailor.

I first met the now 68-year-old last month at The Moorings. He was sitting at the entrance to Sunsail, chatting with some taxi drivers and Moorings employees. I would’ve passed the otherwise unassuming seaman had it not been for his billowy white beard that caught the corner of my eye and turned me around.

“Presley?” I asked.

“You must be Dan,” he responded curiously, cracking a smile. “I thought you’d be older.”

He hoisted himself up with a collapsed umbrella and suggested we talk away from the bustle and noise of the busy marina. I followed the veteran sailor and longtime Moorings employee as he led me to a quiet table near the pool. It was a slow walk across the dining room; Presley led with a wincing hobble and used his umbrella as a crutch to help him along the way. That day his foot bothered him, he told me. He had just returned from a check-up at the BVI Doctor’s office where he was instructed to stay off of his swollen appendage. Similar ailments have troubled Presley since 2003, when he suffered a debilitating stroke that might have forced many in similar situations away from physical activity. But not Presley. He was quick to return to sea and has since participated in several regattas. When asked if the stroke affected his ability to sail, Presley chuckled. “No, no. I just don’t run like I run before,” he said confidently in his jovial West Indian accent.

Today he continues to do maintenance and transport boats for The Moorings. I found out that Presley doesn’t need the agility or reaction time of a young man to navigate his way around a marina or a seaway. His nautical knowledge was inherited—then developed through years of practice.

Presley credits everything he knows about the sea and sailing to his father. At the age of seven, he learned about the ways of the wind, the characteristics of the current and the importance of the moon’s correlation with the sea. When he turned 10, his dad taught him how to build 17-and-a-half-foot-long Bequia sloops called double-enders, which he soon began to race competitively. Three years later, his father built him his own. Since that time, sailing has turned his love for the sea into his livelihood, and the relationship has become impenetrable.

After moving to Tortola and working for his cousin for a short time, Presley took a job running boats from Beef Island and Virgin Gorda for Marina Cay, a BVI development now known as a popular outpost for Pusser’s. During that time, the Bequia-born sailor made a name for himself as a fierce competitor among local salts of the sea.

As we sat at our second meeting at The Moorings, Presley flicked through a photo album filled with pictures from an earlier generation of sailors—sailors who battled on small boats called sunfish and squibs for little more than bragging rights and a Heineken after the race.

El Richardson, a longtime friend of Presley’s, has fond memories of those days. I sat with El at his marine supply shop in Road Town, where he reminisced about a simpler time.

“There was no proper yacht club in the early 1970s—just us guys racing all along here,” he said, motioning across Road Harbour. “Yup. All the way to Paraquita Bay and back.”

Presley was always a figurative pain in the stern as he usually followed closely behind El during match races. El said he usually found a way to weasel a boat length or two ahead of his competition. But during a particular Around Tortola Regatta, it would be all broken dreams for a young El.

“We had him—we were [catching wind] hard, and then crack!” he exclaimed, explaining that their boom had snapped under pressure. “He took us that race. But he didn’t want to beat us like that. He was a competitor—a very good sailor.”

Continuing, El described the “local knowledge” that he and Presley and other resident sailors possessed that gave them an advantage over other traditional sailors. In order to beat Presley, El said he had to enter a “think tank” before races to plan his attack strategy.

“He always had a good attitude,” El chuckled. “I remember we nicknamed him straw hat. He always wore a straw hat.”

El has since retired his racing hat, instead enjoying similar legendary stories from within his store, surrounded by memories of the past. But Presley hasn’t skipped a beat.

Since those days, Presley has sailed in almost every Spring Regatta dating back to its inaugural opening in 1974, missing out only because of his stroke and a brief relocation to the States. He spoke fondly about racing in the Panama Games in 1983, where he crewed on the BVI’s team and placed “in the middle” of a 10-boat pack. In 1992, Presley was selected as an alternate sailor for the Olympic games in Barcelona. He joined Robbie Hirst, John Shirley and Robin Tattersall at the paramount event.

“I was always dreaming about being close to [the Olympics], but there I was—in it,” he said. “I spent a month in Barcelona, where the water is cold but the sun was hot.”

The 1990s were monumental years for Presley, as far as competitive sailing goes. During that time, he won the majority of the Spring Regatta bareboat class races he entered. Bob Phillips, who now chairs the Royal BVI Yacht Club and BVI Spring Regatta, remembers racing against Presley shortly after moving to the territory in 1993.

“He’s just a phenomenally good sailor—very much seat-of-the-pants-type of style,” he said, recalling his unique ability to judge the current by the location of the moon. “I remember one Spring Regatta, we had a real light breeze on a Sunday. [Presley] came to me and said, ‘Bob, you’re not going to have any breeze until right after 11. The moon will be right ahead of you at that time.’ And sure enough, within 10 minutes of 11, the wind picked up.”

Of Presley, the longtime Spring Regatta and Royal BVI Yacht Club chairman said, “I think the world of him.”

Presley has won the affection and admiration of many with his lighthearted outlook on life, his contagious charisma and his ability to hammer down fungi rhythms on a banjo or ukulele. That’s perhaps why so many came together recently to help him during trying financial times. Since his stroke, Presley has incurred large medical fees, and had been forced to take time off work as he was nursed back to health in the States. While there, his longtime partner Pamela Lendzion cared for him after he left the hospital, quitting her job to do so.

“It took a while, but I finally got him back on a boat, and we worked to rebuild those brain cells,&rd

quo; she recalled. “Now he’s sailing just fine, doing deliveries, still racing. It’s a miracle.”

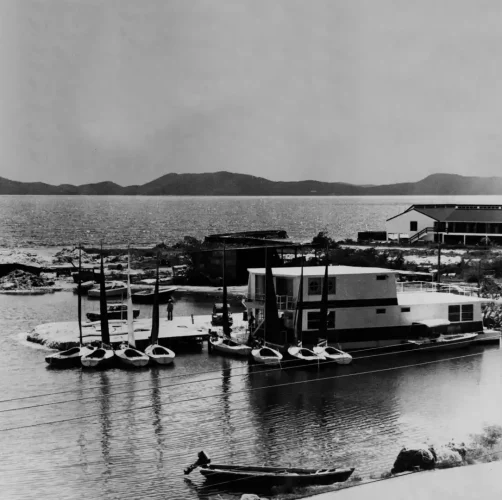

Although they spent a couple years near the water in New Jersey and Florida, Presley missed the islands—the people and the familiar warm waters. Moving back, though, on a $300-a-month social security check, has been close to impossible without the help of his friends. Friends like Bob Grannafei and Sandra Jarett, who organized a group to donate to the cause and refurbish an old boat for Presley to live on. Several friends have gifted their time, equipment and money toward the project which has since afforded Presley the comfort of a new home on the water, docked appropriately at The Moorings, where he now lives the life he was always meant to live.

As I sat at that peaceful Moorings table discussing Presley’s life, it was evident that the lifetime seaman had a lot more living—and sailing—to do. Physically, Presley wouldn’t admit much has changed since his stroke. But spiritually, he said he has developed a closer relationship with God. He admitted to a few regrets and relationships that needed mending—but always lit up as he took me through his fond memories of sailing.

“I don’t have much—gave everything away accept my ukulele, and I can’t even play that.” he admitted, clenching and releasing his left hand. “But other than that, I’m doin’ fine.”