Of the BVI Economy

Dr Michael O’Neal’s book Slavery, Smallholding and Tourism: Social Transformation in the British Virgin Islands was published this year by Louisiana law publishing company Quid Pro Books as a part of its Classic Dissertation Series. During his launch of the book at Island Services in Pasea, Dr O’Neal remarked that the publishing house was interested in his dissertation “because of the substantial use of court records with respect to the plantation era.”

The book is valuable not only for the court records but also for its insightful coverage of several transformative periods in the BVI—the plantation era, the post-emancipation era and the beginnings of a tourism-based economy. Though published this year, Dr O’Neal’s dissertation was written in 1983, one year before the passage of the International Business Companies Act of 1984, so the final section of the book serves as a snapshot of the territory when it was on the cusp of prosperity resulting from the boom of the financial services sector in the BVI.

The most striking contribution to this snapshot comes from Chapter five of the book: “Perceptions of Tourism and Development.” This chapter includes transcripts of proceedings from a symposium held in 1982 with the topic of “Social Change: Implications for the British Virgin Islands.” The symposium, Dr O’Neal writes, was part of his doctoral internship, and “affords perspicuous insight into British Virgin Islanders’ perceptions about their existential circumstances” (p.97). Highlights from the transcript include McWelling Todman’s account of the years leading up to 1982—a history that puts the state of affairs at that time into perspective with relation to tourism development and truly shows the BVI’s economic climate as being concerned mostly with tourism and only briefly mentioning (within the context of the length of the monologue) “foreign exchange contracts” and “Trust Companies” (p.102, 103). In a recent interview with VIPY, Dr O’Neal said, “The 1982 symposium provided a forum (probably the first of its kind at the time) in which a convocation of academics, technocrats and policy-makers, comprising both BVIslanders and invited guests, gathered to discuss the perceived social impacts that had been concomitant with the dramatic social changes which had occurred in the BVI.”

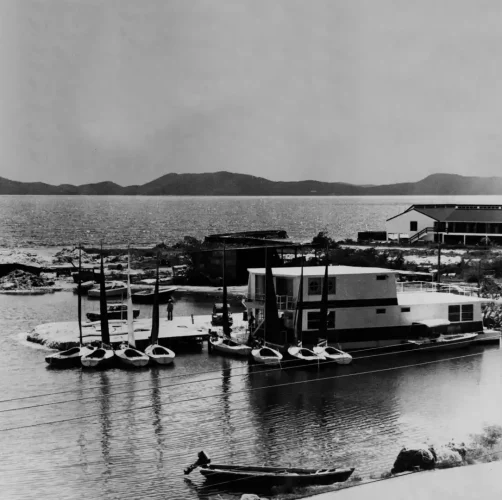

The book also highlights the importance of the Positive Action Movement of the late 1960s—a series of protests against Government regarding the development of land in Wickhams Cay I and Anegada by Batehill Ltd. The importance of the Positive Action Movement was that it vocalized “widespread discontent over the Wickham’s Cay-Anegada Agreements, as well as concern over what was being perceived as uncontrolled development” and resulted in the Government abrogating the Agreements and acquiring the Batheill Ltd interests (p.90). The outcry of the community against the development resulted in the Government’s reassessment of its tourism/development strategy that focused on sustainable development and an emphasis “on developing the Territory’s marine resources” (p.91). Dr O’Neal recently said, “The abrogation of the Batehill Development Agreements coincided with the 1970s recession in much of the Western world, a period with some similarity to today’s economy. This was also a time for reassessment for the BVI in terms of development strategy and direction, which, in the event, resulted in a strategy of carving a niche in marine-based, charter-boat tourism, along with some sensibilities regarding a sustainable development approach, as noted.”

Bill Maurer’s Afterword to the book concludes with a focus on the financial services industry within the historical context that Dr O’Neal set up with the plantation era, post-plantation era and tourism-based economies. The question Maurer asks, based on this framework, deals with the continued exploitation of the BVI. “If the BVI remains today a colony of exploitation,” he writes, “how does it do so, in what direction, and who is exploiting whom?” (p.137). Dr O’Neal asserted during the book launch that he wrote the text as “plea for a sense of historical perspective” for the generation at the time. The final sentence of his text warns against “the centripetal force of a mode of development which, in the long run, is completely homogenizing.”

Thirty years ago, during the tourism symposium, one speaker, BVIslander Anne Kortright suggested that it was only a matter of time before BVIslanders were “swept away” and repeated the “unplanned growth” of other islands. Thirty years after Slavery, Smallholding and Tourism was written, the BVI remains free of franchises, has not been overrun with skyscraper hotels, and maintains a pride of land ownership.

“The BVI is again at a similar inflection point, both in terms of the worldwide economic environment of recession in which it operates,” Dr O’Neal expressed to VIPY, “and the need to determine its development strategy and direction, with such critical issues to be decided as the notions of airport expansion, cruise ship infrastructure development, and so on.”

With its court records, symposium transcripts and virtual time capsule of a subject matter, Dr O’Neal’s book provides a valuable history lesson for those interested in the future of the British Virgin Islands.